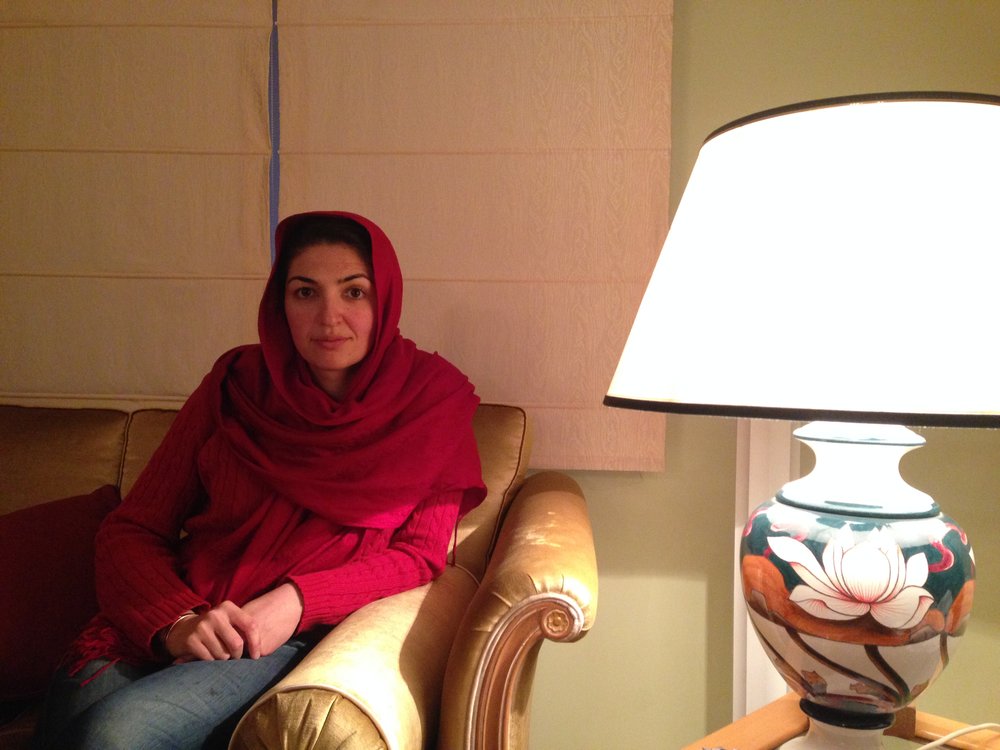

Gelareh Kiazand: Kiarostami’s Student Taking the Documentary Scene by Storm

TEHRAN - Thus far in her career, the young Iranian documentary maker, Gelareh Kiazand, has attained herself a prominent reputation in delving into issues that affect the most deprived of the world’s population but of which rarely anyone ever dares to make documentaries about.

Gelareh has worked in major Hollywood film productions alongside the likes of Brad Pitt, Bill Murray, and Tina Fey, but it is her independently directed documentaries around sensitive topics such as child suicide bombers, women’s rights, climate change, and fading cultural heritages that have caught the eye of the world.

Gelareh meets me at her residence in Tehran with the kind of cordiality that you would get if you had known someone since high school; in reality we have known each other for less than 48 hours. From the first instance I can tell she isn’t in the film business for any other reason but for her honest, pure, and raw love for anthropology through the intuitive lens of the camera. She describes herself as a ‘visual person’ that uses camera as an empowering tool to portray events of importance to her.

As we sit down to begin the interview, Gelareh tells me a little about her nomadic upbringing: she was born in Tehran right after the Islamic Revolution in 1981; she emigrated with her parents to Dubai not too long after and was brought up between Abu Dhabi, London, and Toronto.

But then, she chose different: “I left Toronto for Iran because I wanted to know more about this culture,” she gestures towards the house, “my parents’ choices of food, literature, music, it all came from Iran, and I was very drawn to see where I’m from.”

And where she is from, indeed, rewarded her curiosity and diligence with dear experiences beyond what she initially imagined. She came to Iran in 2003 and worked as a low-paid amateur photographer until she got involved in circles that propelled her with a notable project with the late renowned filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami.

Gelareh recalls Kiarostami with immense warmth: “He was such a profound man. Spoke so few words, but they meant a lot,” she answers with a heavy sigh.

Gelareh went on to photograph all the portraits of the actresses that appeared in Kiarostami’s film Shirin (2008) at the tender age of 27 and reminisces Kiarostami as “an uncle and a mentor” that was there for her until his death, which she regards as “tragic”.

I ask if Kiarostami has influenced her work and she gives me a convincing nod, later telling me how Kiarostami had not only influenced her work but also affected her life. “He was very into sharing his knowledge,” she evokes, “and we need more people like him – people that build bridges.” That seems to be the kind of an unorthodox direction Gelareh has decided to swing her own career, too – to build bridges between cultures by delivering the untold stories of the people that do not have the means to do so by themselves.

“You look at countries like Afghanistan, India, Turkey, and Iran, and they have great stories to be told. We need to tell more of their stories to the world for there to be a better understanding of the societies that co-exist,” Gelareh asserts.

Gelareh has sacrificed her own safety by travelling to the most dangerous, war-torn and high-risk territories in the world simply to deliver the perspective of the people that would otherwise never get to be heard of. She moved to Afghanistan in 2010 when the country was still untouched, as she recalls it, and had people pouring in from every corner of the world to “bring in some change”. She was in Kabul when she started collaborating with Shane Smith, the CEO of VICE Media, in filming a pilot for HBO about child suicide bombers. The pilot premiered to solid ratings and became an audience hit, landing a deal for future episodes.

But the longer she stayed in Afghanistan, the more the state of the country was deteriorating with the threat of Taliban breathing on her neck. When she continued her filming onwards to Kandahar, she was embedded with the military due to security concerns. Not only was she a white foreigner in a country divided by terror, fear, and insecurities, but because she also happened to be an eye-catching, tall, fresh-faced, curious and inquisitive woman – precisely that, her gender – that she had to be protected to a greater extend.

During the time she was in Afghanistan, Gelareh faced discrimination and denigration because of being a female documentary maker, and was once even called out to be ‘a man’ by an Afghan gambler purely because she was attempting to film an illegal blood sport [dog fighting] in Kabul. But she has an open, almost psychoanalytical, approach to handling these incidents: “I thought it was interesting to see how they would accept me to hang around only if I was, partially at least, male.”

I wonder if she thinks her occupation would be any easier if she was a man, to which she answers with a tentative laugh that she wouldn’t know because she has never been a man. To interpret her answer in the context of her attitude that gender alone cannot preclude a successful career, one can see that Gelareh in fact leverages her position as a female documentary maker in situations that most of us wouldn’t want to find ourselves in. “It’s just harder to prove that you’re capable of certain things,” she states further. As a woman, however, she admits that she is able to get to the “sensitive side of people [where] their real reactions come out”.

To get the real side of people, Gelareh has gone through hell and back. In Turkey, she followed a group of children that had been brought up knowing their fathers had killed their mothers in an act of vengeance after divorce – a trend that had seen a peculiar rise in Turkey between the years of 2002 and 2009. She wanted to know if such an upbringing instigated more violence in a society, but she was unable to reach concrete results and had to leave the project incomplete. In India, she filmed the journey of several women in one of the most destitute regions of the country that went onto form a group – the Golabi gang – as an expression of collective force to protest against the negligence of the legal system that had turned a blind eye to the soaring numbers of rape and sexual assault incidents in India, where the victims were often from the most disadvantaged parts of the society.

For Gelareh, the time has come to turn the cameras on Iran; this time, though, she wants to highlight the importance of preserving our cultural heritage in the age of globalization and rampant influences. She tells me a story about a couple she met in Kurdistan that had been gathering the most beautiful and antique fabrics around Iran and were attempting to get the attention of the mainstream fashion industry with them. “I was very moved by that,” she says enthusiastically. “Their story should be told,” she adds, “if it wasn’t for people like them that try to save handicrafts, traditions and our culture, we’d be lost.”

Though very subtle in person, there is not a doubt that Gelareh has a ferocious ambition lying behind all these years consisting of fearless work, travel and research. I wonder, Gelareh being an insider that looks at things often through the camera’s omnipresent perspective, what intrigues her and what worries her at the moment.

“In Iran, globalization is playing a major role,” Gelareh remarks. “People are leaving villages and coming to cities thinking the real life is here,” she ruminates, “but I hope that we can preserve the smaller communities [of villages] and the culture, instead of them trying to become us.”

As we are reaching the end of our interview, I ask her what does she has lined up for the near future. She shifts her voice and resumes her focus, as if about to confess something, before telling me it’s a project very close to her heart. Upon inquiring more, she responds that it will be about human survival stories and how people survive based on their own understanding of their surroundings. I want to know if she has found a particular way to survival after all the risky circumstances that she has been through. She inhales deep, and with insatiable credence, affirms, “live a life that is more than pushing buttons”.

Leave a Comment